5) Knife in the Water (1962) Dir: Roman Polanski Date Released: October 1963 Date Seen: January 8, 2010 Rating: 3.25/5

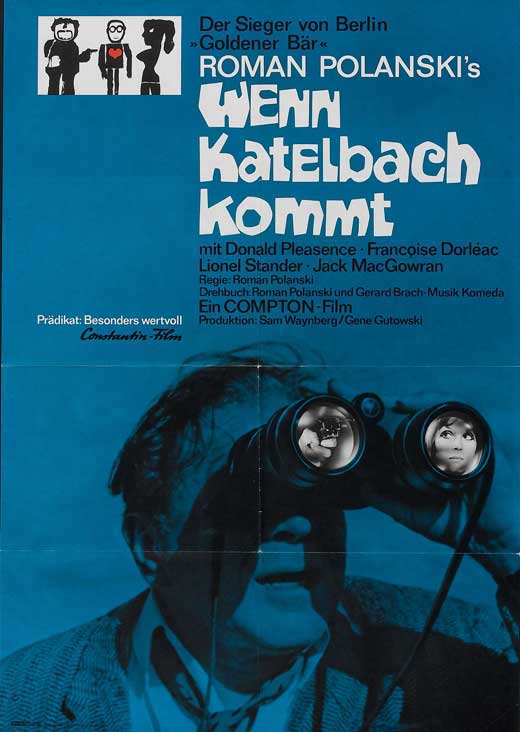

6) The Fearless Vampire Killers (1967) Dir: Roman Polanski Date Released: November 1967 Date Seen: January 8, 2010 Rating: 3.5/5

7) The Tenant (1976) Dir: Roman Polanski Date Released: June 1976 Date Seen: January 8, 2010 Rating: 4/5

When I originally planned yesterday's Polanski triple bill, I had no intention of analyzing the well-regarded filmmaker's controversial personal life. I already know what I think of what he did and I don't particularly want to judge the man for it. The half-baked notion of using the artistic merits of his films to balance the scales of my personal judgment of his actions never crossed my mind. In all honesty, I was just looking for two other films to go with Polanski's The Fearless Vampire Killers, which I had recently bought with a gift card. I had had my eye on Knife in the Water and The Tenant for some time, so whammo, there you have it.

What I didn't expect to find in these films is an overt, semi-self-deprecating and always playful act of mock-self-analysis. Knife in the Water in particular seems like a film about a young man, credited as "Young boy" (Zygmunt Malanowicz), coming to terms with the fact that he secretly wants to become the bourgeois authority figures that he vocally resents. He's told as much by his would-be conquest Krystyna (Jolanta Umecka), who mostly smirks quietly in the corner over the course of the film, knowing that her husband Andrzej (Leon Niemczyk) and "Boy" are fighting over her. Because she rarely speaks at all, it should be noted that this one time she says anything truly revealing is all about "Boy" and not her. Considering how the film is mostly comprised of blunt but comparatively delicate exchanges between the brash "Boy" and the domineering, reactionary Andrzej, Krystyna's thunderous outburst, characteristically scripted in broad strokes by Jerzy Skolimowski, brings the film's house of cards down on top of "Boy"'s head. Here's his secret fantasy of attaining Andrzej's status without his preening attitude in ruins, a daydream that ends as abruptly as it began ("Boy" practically becomes Andrzej's sedan's hood ornament when he tries to flag him down by standing squarely in the middle of a dirt road).

Taken on its own terms, Knife in the Water's tendency to focus on "Young Boy" may not suggest an autobiographical link to Polanski but it does reveal a lot about his regular preoccupations with sexually incompetent tyros. "Boy" craves Kyrstyna's attention but she shoots him down by sizing him up as quick as you can snap your fingers. He can't have her because he can't face the fact that he's not mature enough to do everything he thinks he can. His laughably egomaniacal self-image as a Christ-like journeyman that can literally walk on water is his undoing.

The same is true of Alfred, the apprentice character Polanski plays in The Fearless Vampire Killers. To overcome his clammy sexual insecurities, which manifest in the form of his failure to stake the vampires that his wizened old master Prof. Abrsonsius (Jack MacGowran, made up to look like a rejected Asterix character) commands him to, Alfred becomes obsessed with rescuing the buxom Sarah (Sharon Tate), the local inn-keeper's buxom daughter. This misguided sense of chivalry ends up getting him turned into a vampire, as the film's mischievously booming voiceover narration states in no uncertain terms ("Thanks to him, this evil would at last be able to spread across the world," it says about Abronsius, but realistically, Alfred is the one to blame).

That heavy-handed narration is striking as it's not seen or heard throughout the film, only bookending its events. One of it's more telling insights to the film's events comes when it tells us that Alfred is "under-appreciated" in his work, which is funny considering how inept he is at it in the film. This is best expressed in the film's slapstick humor, which reap the best gags in Polanski's otherwise lopsided comedy (the set pieces are all marvelous but the film is more than a little drawn-out). He craves recognition very badly but he's clearly not worthy of any just yet.

Still, of the film's many displays of Alfred's absurd impotence, one gag stands out: his seduction by a gay vampire, whose effeminate singing entrances Alfred but only until he discovers the gender of the idle crooner. I might be able to dismiss Polanski's attitude toward the character as a one-off gag but the gay vamp's father sarcastically mocks him as a "a gentle, sensitive youth," hinting at an ugly kind of apathetic intolerance that only finds further expression in The Tenant, in which Trelkovsky (again, Polanski) goes mad and winds up cross-dressing because of his rampant persecution complex. This is intended to be one of the many cruelly funny manifestations of Trelkovsky's urban paranoia, the kind that drives him insane with the whispers of nosy neighbors, both real and imagined, but it just comes across as a thoughtlessly bigoted slap in the viewer's face.

That having been said, The Tenant is probably one of my favorite of Polanski's films, right behind Chinatown but above Rosemary's Baby. It has a pervasive sense of black humor, which kicks into overdrive in the film's masterfully obnoxious ending, that nicely tempers the film's heady depiction of Trelkovsky as a far-too acquiescent young cave/apartment-dwelling urbanite struggling in vain to establish a sustainable social community for himself. He fails and it drives him out of his mind and his window (twice) and when it does, he wails so abrasively that it's hard to imagine who in their right mind imagined the film as a straight-faced thriller (No hot chocolate for this man; just give him the coffee!). In its non-chalant brutality, its merciless execution and its cast's skillfully heavy-handed performances, The Tenant wrings out buckets of the kind of squeamish humor that seems so ill-fitting in Rosemary's Baby's balloon-buster of an ending ("All hail Satan," indeed). It's not as elegantly simple as Repulsion but in its cynical ambition to completely crush Polanski's young avatar, it's pretty staggering.